[(notes)

Writing a book.

Which has:

A woman who escapes. An escapee. She has run away. A woman who left her life who and will have nothing more to do with it (see below) except in memory, e.g. flashback, despite the fact that it (meaning him, see below) will, from time to time, intrude into the story as it is happening in real, e.g. fictional time. And because of all the elements in the story there will be an amazing denouement.

The ex-husband who is a psychopath: he really is. Or he is really warped. Warped to the point of being destructive. Nothing against ex-husbands at all except for this one, who is the be-all and the end-all of ex’s.

The writer standing back, standing back, standing back, drinking coffee, sitting down, drinking coffee, wearing down her keyboard so you can’t read the letters, particularly e, t, r, a, i, o and the right portion of the space bar is worn down the same way—what is her chemical problem, is it the coffee?

The writer standing back, standing back, standing back, drinking coffee, sitting down, drinking coffee, wearing down her keyboard so you can’t read the letters, particularly e, t, r, a, i, o and the right portion of the space bar is worn down the same way—what is her chemical problem, is it the coffee?

Canines, but not dogs, except as a kind of genetic accident. In this book there are wolves. Wolves. This is not a dog story. This is a wolf story.

A past intruding as always, colliding as usual, receding like a hairline in an older man

An older man who is so remarkable that he does not actually have a receding hairline

Sex

Lying next to the man and resting on his shoulder, which is perfectly structured so as to be able to lie on it, to sleep, finally.

Sleep. To sleep like a wolf.

Food, such as pancakes, which requires the presence of a diner, which requires a waitress, who is not just a foil making conversation but an ex, possibly, of the remarkable man, but also listens, listens, pours, brings, hefts, wears soft soled shoes, a waitress dress, a headband. She is slim from working, wrinkled from time, age, cigarettes, bad diner air, possibly trailer air.

This is in the mountains. The woman, the main one, the protagonist, she lived to the south, just a bit to the south. And when she escaped, she raced up north, blindly, nearly, in a badly maintained truck that turned out to be a one-way ticket.

Things badly cared for do not always last the entire designated arc of their life.

There are wolves and they are badly cared for if you can even say that. And then they are stolen from their county fair cages and backyard cages and game farm jails and basements and dog shelter chainlink by this group who rescues them. And then they are well cared for. Which involves carcasses. Lots of meat. Chunks. Frozen giant chunks being rolled around on ATVs.

So I can write,

Still in her nightgown, Rena strapped the frozen horse leg to the back of the ATV and started down the hill to the juvenile enclosure. But she’d forgotten the chainsaw. She’d have to turn around. She’d have to get down the hill before she could turn the ATV around. She unstrapped the horse leg and let it fall to the ground, right in front of the enclosure. Hal had said, if they’re hungry enough, they’ll climb the fence.

Don’t climb the fence, Rena said to the juveniles, who were now pacing the length of it, eyeing that leg.

(I love horses. This may be hard in the long run, to set up the wherewithal whereby people can get horses to feed to the wolves. Old horses, brokedown horses. Horses who died in the field. Racehorses with shattered legs. I tend to forget how hard things can be, in the long run. Perhaps I have lived my life with blinders on.

Speaking of blinders and eating there are many ex’s, actually. This man, the older man with the perfectly structured shoulders in terms of their being the perfect height for her to rest her head and actually sleep, he got around before he met her.

Whose name is Rena.

And the truth is this is a character I have held dear for a long time, ever since I discovered her, freezing in a bathtub, after a bad thing had just happened. And this was in an earlier part of her life, in Maine, where she got into a lot of trouble, or was swept up into the tides of other peoples trouble, where she was living in contradiction to her parents’ belief that since she was well educated and the daughter of self-made strivers, she ought to have a good—as in sensible, as in boring—head on her shoulders.

And so she took a long and winding road to trying to hold down jobs, to wear clean and uninteresting clothing bought from stores, to being respectable.

And one night, driving too fast in that badly maintained little truck to get away from the husband she had married by mistake (grabbing for that gold ring, that humming circle containing the family and the future she wanted—when in fact there was a black hole dwelling in that ring, a vortex, a rude slap in the face of a woman’s most basic assumptions and hopes for herself—one night, while she’s driving too fast and heading north, the story starts.

Not begins. Starts. Like a shudder, like an engine, like a heart.]

1

When Rena slammed the front door and left the house for what would pretty much be the last time, except for coming in to fail to negotiate with him or to grab more of her things, it was already snowing. It was a kind of wet and sparkling snow, an avid but not very substantial or effective snow, a kind of mystical screen that appeared only where light shafted into the night. And in her state of mind the snow was mocking her, her over-serious intolerance of the situation she’d slammed back into the house. Behind their front door, which opened into the living room—as this was a farmhouse built in eighteen-ought-eight and they didn’t make front halls in these parts, just places big enough to hang up the side of the pig you’d just slaughtered—behind that door, that authentic olden days in olde New York state door, board and batten they called it in realtor high-gloss—she’d left two people.

One of those people was her husband, in his black velour bathrobe and brand new Hefner-esque pajamas, his thinning hair combed Romeo-style back away from his calculating knob of a forehead. She’d left him sitting on the couch, not at one end but towards the middle, towards the other person. And the other person was that Philadelphia girl, the art student, imported here by way of the internet to celebrate his midlife crisis. Are you sure it’s all right? Are you sure? Because it’s such a dream of mine, it’s really always been something I hoped I might someday get to experience and I’d be so happy just to do it once, just once, just this once, and have it be a happy memory. And I know you understand that, how I want this, you’re such a wonderful wife to understand that—

She had nothing against art students. She’d been one—actually an art minor—decades ago, in college. She knew all about Derrida and perspective and gouache. But this girl, she was young. She was daughter-young. And yet she a particular kind of whatever, it’s all just an art project anyway attitude that pressed all sorts of buttons. The girl acted so blasé about coming up on the bus at the invitation of someone, some man, she’d never met. She had no fear for her own safety. And no qualms about what he wanted her to do, no qualms at all. And it was being faced with this art student who had no qualms about her husband, and faced with her husband who had no qualms about the art student, and faced with the groaning sideboard laden with meats and cheeses and medieval looking fruits that he’d laid out, and the honey he’d puddled between the ripe fruit, so as to convey a heightened sense of decadence and luxury and open-mindedness—let’s just all ooze into it, shall we—that was the opposite to how Rena felt that day, when it was finally that day. And she just snapped. The hazy drapery of not really thinking about it for all those weeks before—there was always something else to think about, deadlines, work, money—as he’d gotten more and more excited, couldn’t stop talking about it—the heavy cloak she’d seemed to hang up between her and it just crashed to the floor. Everything was thrown into a stark and clinical and—sure, why not, she supposed, she’d own it this time—puritanical light.

And there she was. She was standing in the middle of their living room with its shadowy corners, with its weak lamps, smelling that fussy incense he’d lit again, and his special occasion cologne, and some kind of synthetic berry scent from the girl—she wasn’t going to even get close to that—and the cheese melting and wine evaporating into the overheated room, and the wood in the fireplace, scorching in the starving flames—and behind all that, the mildew inside the walls, the mouse nests, the everything—

“Honey, would you like to show Kumi the rest of our house?”

“Honey?”

“Kumi, wouldn’t you like to see our house?”

“Of course,” said Kumi. “I would love to see your house.”

Like a children’s book. Like a script, like an excuse, like a lie—

“Oh,” she’d said. Not to Kumi or her husband really. Really more to the house. Said, “I need to go outside. I really need to get some air.”

They stood there, the two of them, looking at her. Placid as cows in their favorite pasture.

“I need air,” Rena said. “I need—I am just—sorry,” she said. “I’m sorry—”

To leave required grabbing things, which required finding them. Which required concentrating in the midst of the riot in her head. Truck keys—on the coffee table right next to her, there were the keys to the truck. The truck, for some reason, not their car. There was her bag sitting on the chair where she’d thrown it, containing wallet, containing possibly hopefully money, a pair of gloves, loose change hibernating in the seams. There was the phone, and this was odd—she spotted it tucked beneath the rim of the bowl of ripe figs on the sideboard, as if were swifted away, as if to be out of reach. Coat – she nearly grabbed the girl’s, some pink flirt of a silly jacket, then nearly his big wool shapeless old thing, then found hers, the biggest one she owned, the old big puffy coat with the hood, big enough to sleep in. And then she grabbed a scarf, and another coat that seemed like it might repel water, or at least snow. And then grabbed something on the table by the door – a drinking glass, for some reason she grabbed that, grabbed the framed picture off the wall, the picture of tree bark—she’d photographed and framed tree bark when they moved up here and now it made some kind of sense to grab it, to take it away from all this. And then, hands filled, she somehow got the door open and then got on the other side of it in the ice-cold air of the night, and then slammed the door shut behind her with her foot.

Even as she did all this, she was in such a state that she could see herself, feel herself, watch herself doing it all. The fury of it. The end of it. The absolute indignant I can’t do this of it. The I’m not buying your midlife crisis gimmick, the I won’t fork over all my money into that mystery pit you call a joint account anymore of it, the you want to do what?! of it. The I won’t strike that bargain you somehow coerced me to nearly strike. She watched her hatless head nearly bang itself on the rim of the truck window, she watched her hands flurry a hat onto her head, her frizzy, just showered, make a good impression—for what ridiculous reason she didn’t know—hair, the big red beaded earrings she’d hooked into her ears, swinging like stoplights in a hurricane. She knew she was overblown already but there was no stopping it, this roar of everything at once, and yet she felt so far away, like she was sitting on top of a star looking down at this woman in a fury.

And this woman was starting up the truck. And there was a man was yelling through the window. And he would not even open this window. He was yelling through the steamy glass, he was a big, pink, open mouth, would not even open the damn front door—of course, how obsessed he always was about keeping the heat in, don’t waste an ounce, don’t let it lower one single nth degree—And Philadelphia Girl was standing behind him like she was already his best pal, she in her sailor dress and over the knee white socks, her pink girlish glossy, sticky pout. The two of them were inside the house together as they were watched her outside the house pulling out of the driveway, jerking a three point backwards turn and nearly toppling the woodpile, and then she peeled out.

She drove down their road, the long wavering black canyon of it, just an old oxen lane turned into something drivable, a quiet ribbon strung between the hunched shoulders of the mountains on either side. The houses were all dark and empty. It was the middle of the week. The houses were all owned by weekenders who dressed in L.L.Bean with the creases still in as they strode around with their pedigreed dogs—the houses, really, like a reason to get more L.L.Bean, to dip into the home section, get those madras coverlets. The snow was sprinkling, still, all over the night, and seemed to sift down from the sky right over the truck like sugar caught in the headlights. It was such ridiculously lighthearted snow and Rena was so lightheaded. I had a big gulp of that wine, she remembered as she veered onto the main drag, heading north into the night. The right turn did it, nearly brought back up that Chilean blood red wine he’d bought, the meaty-tasting stuff. She’d nearly gone through with this thing, and had taken a gulp of wine as if she could drug herself into it but she couldn’t and she didn’t, and now it was snowing harder and she had a full tank of gas and the truck’s tires did not seem to really want to have a meaningful discussion with the slick road-top. And why hadn’t she taken the car, the four wheel drive Japanese model mini-SUV wagon thing—she was always being so damn considerate because she was so used to his saying that he liked to take the car, that since he drove longer distances he should really be the one to use the car—

There was no one on the road. Wednesday night 11 pm heading north toward the higher elevations and who knows what. The truck did not have power steering. She thought for a moment that she should go back, and switch the truck for the car. She could wheel the truck around in the parking lot of the old empty restaurant up at the junction. But who knows what she’d find if she returned to the house, to their house. Maybe he’d just be waiting there, ready to dismiss her flight as an act of nerves, as an impulse, as actually kind of selfish considering she’d promised, hasn’t she promised him? Whatever. Or he might just be there conducting himself as if nothing had happened, getting his just like a young man feeling on with Omiko. Was that her name? Omiko? Komiko? And what giant bird, or something, just flew across the road and right over her windshield? Or maybe if she pulled up and got out, he’d be ready for her with some kind of wild animal net, waiting to bag the runaway wife and drag her back into his ridiculous fantasy.

She couldn’t risk it. There was no turning back. She felt a kind of thump, somewhere between her heart and her stomach. A palpable cinderblock sank down and lodged itself there. But she kept driving. Two hands on the wheel and half a brain and all this adrenaline and a tank of gas. She headed towards the junction with the old turnpike, thinking again about that bird – an owl? Didn’t owls hunt at night? This thing had been huge. Were owls that big? There was a whole wild world out here. Rather be with you, she said to the night, the navy blue sky and the winking moon coming back out. The snow was letting up. It felt like it was giving her some kind of reprieve, some kind of consent: Drive. You are hereby welcome and justified to drive.

There were a few problems, to be honest, with her plan. 1) It wasn’t a plan. 2) She had no idea where she was going or ought to go, and the only place she might have gone, which would have been south, either to cousins in Westchester or family in Manhattan, she would never do. She never, truthfully, wanted to go back to the city ever. 3) Those two things really didn’t matter to her at all, which meant it was all up for grabs by the hands of fate. It was anarchy waiting by the side of the road.

There was another problem. She wasn’t much of a driver these days. She’d had an inner ear problem, an infection, and it had made her wonky for a while and a doctor had said, well, maybe no solitary long road trips for a while. And everyone: her husband, his family, her family, even she – had taken it to heart like an official edict. So she was rusty. She didn’t have any road nerves. She didn’t have that mile after mile thing in her anymore, that blacktop endurance. And so, after 115 minutes of heading north into the night, heading north because that’s what happened when she turned right and then right again and then left, after 115 minutes of heading north into the night where there were few if any streetlights and only a few cars, and mostly she was alone with the thrum of the truck’s slightly geriatric motor and the empty open space of the road slotting into the night, she began to get sleepy.

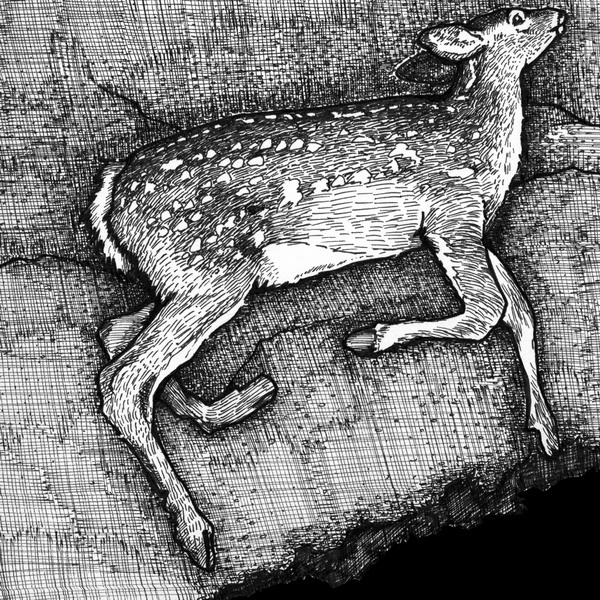

She hadn’t eaten, either. Had she been on foot, she thought, had she been an animal, such as a deer, she probably would have slowed down from her prey animal run to a trot and then wandered into a midnight glade and found a nice place to curl up and lie down. Lie down beneath the shelter of some bayberry, some hemlock, something feathery and sheltering. And she must have thought that for a reason that had more to do with being aware, as in—wake up. Because just as she began to imagine that little Bambi scenario, she realized there was really was a deer—the body of a deer and the ears and eyes and hooves of a deer hovering in midair just above the hood of the truck, just in front of her. And the deer was about to hit the truck and the truck was about to hit the deer and whoomp. Bump. Mass colliding with mass, some kind of velocity factored in, and all happening so fast—

The truck spun around so it was facing the opposite direction and then it stopped. She sat, hands gripped around the steering wheel, melted into the wheel is how they felt. Like she had no hands. She tapped her left foot. She tapped her right. The truck lurched and she pressed back down on the brake. So I stopped, she thought. Something about that fact gave her some kind of odd hope just then. That brain-body connection, however shaky, it was still there. And in the headlights, right in front of what should have been behind her, in the frittering, fickle little pattern the snow made, was the deer. It was lying on its side, back wedged against the guardrail that kept it from sliding off the edge of the road. In the blast of her brights it was all white. A phantom deer. She flicked off the brights and the deer was a white belly and brown around it. It lay there, long legs resting toward the road, pointing at the road. She couldn’t see any blood. She couldn’t really see its head. She had no idea if she’d mortally wounded it or killed it. But suddenly it mattered terribly that she didn’t.

She sat there, shut off the truck’s motor and keyed on the lights. The radio came on, a country station. She hadn’t remembered listening to any music really, didn’t want to, it was like a bad smell and she shut it off. The quiet was a heavy quiet. A steamy quiet. She kept her eyes on the deer. It seemed like its flank was rising, and falling, ribs stretching to take in air. A leg kicked out and then stopped. Its neck was under the rail, and it shifted, and then the deer raised its head, and there was no blood.

“I’ll get help,” she said out loud in the little cavern of her truck. “There will be someone, there will be help, and I’m really sorry, I’ll fix you. I promise. I do.”

She had no idea if she was hurt. But she found herself flagging down a set of headlights, and she was on her feet, and so therefore she realized that she must be intact enough to scream you fucker as the car zoomed around her and raced away.

“What are you, from the city?” she yelled. And then she looked at the deer. “Oh,” she said. “So sorry. You’re probably upset enough without my yelling, really.” A few minutes went by. She dug around in the back seat and found a blanket, and walked over to the deer and lay it on the animal’s slender legs. The sight of the metal of the guardrail against its skin, digging, possibly, into its flesh was awful, horrible, too much, and it took about five seconds before Rena started to cry. This is what happens when, this is what happens because. She couldn’t even say what when was. When what? Because what? And she was standing there wiping her face with a mitten thinking, Well here I am, a runaway woman on an empty road having wasted a deer in her haste and here I am and just call me bereft when another set of lights came by, set up high above the road. She jumped out into the lane to flag it down, waving her bare hands and gesturing towards the deer, all lit up by the headlights of her wounded, southern facing truck, and miracle of miracles, the creature that possessed such headlights began to slow down and pulled up behind her and stopped.

It was a giant truck. A giant pickup truck. It had an engine that rattled slightly, and thrummed as if flexing its muscle. It sat high up off the ground, and had an ornate auto-body painting of what looked like a pack of wolves chasing a comet past a mountain range under the stars. So she was about to get aid from a local dolt with a sentimental streak, she thought.

“You’re going to kill someone like this,” the man who got out of the truck said, and then said it again and again. He was tall. He was wearing insulated bib overalls and a giant flannel shirt-jac over that. His feet were stuck into enormous insulated snow boots. He was wearing a hunter’s cap with fleece earflaps that dangled at the sides of his face. The cap was too small. He looked a little professorial, wearing gold rimmed, little round glasses. He was in need of a shave. “You’re going to kill someone doing that,” he said again as he stood there. She saw a bit of silver hair shanking out around the hat. Maybe six feet, maybe more. Maybe 50, maybe more. And he’d stopped, hadn’t he.

“What the hell,” he said. “In the middle of the night like this.”

“Thank you,” she said.

[(notes)

Most of us live outside of nature. Nature is road kill. The proof is everywhere. E.g. the apple juice I am drinking is made from concentrate that originated in Turkey / New Zealand, according to the stamp on the bottle. It is organic apple juice. The brand is “full circle.” The brand logo is a circle divided into thirds with a target in the middle. The thirds are grass (green), water (blue), and dirt (brown). The target is supposed to be the sun (yellow). There is a slogan, in tiny, nearly unreadable letters, smiling along the bottom of the circle: Return to a natural way of living. The bottle is plastic. The apple juice involves a trip around the world. Container ships, most likely, belching out waste into the ocean in which there are now tar balls, plastic bag vortices, dead zones, oil. A more natural way of living. Does that require us to be more what?

Wolves: are narrower and taller than dogs. Temple Grandin (Animals in Translation, p. 86) makes the point that dogs are just immature wolves, genetically: they are mapped to stop maturing whereas a wolf will keep on going. That the more a dog resembles a wolf, the more wolflike it will be. The DNA that makes a pup’s nose nice and soft and unpointy is the same DNA that keeps a pug’s nose from becoming unpointy, bastardized, like the apple juice, until there is nothing natural about it. A pug is to apple juice what a wolf is to an apple growing on a wild apple tree. Are there wild apple trees? Up where the story takes place, there were once vast fields of apple trees, and deer to eat them, and wolves to eat those. How do we make a full circle back to a wolf?]

• Include an apple orchard somewhere in the story, an old one, where the deer come to eat, etc. That is the one question I can’t get an answer to, yet: it seems like the only taboo in wolfkeeping. Do they ever eat something alive?

Oh no, said a man to me, speaking on a digital phone from Colorado. That would be, that would be like, like—playing God.

And then the inevitable: So you believe in God then

I do. But I know, how can God permit aerial gunning? My son asked me that the other day. My son. He’s 10.

• Include children in the story: how they are affected, how they act, as part of a kind of communal, giant, fervid community whose mission is to rescue wolves and return them to a wilder (wild-er, not wild, this is reality here) state. Do they draw what Mommy and Daddy did last night in school?

Bobby, show me your drawing. Class, see what Bobby did?

Last night Mommy and Daddy went to the fair and took the white wolf out of the box and then we drove so fast while the wolf was sleeping and the man chased us.

• Include law and police and risk of course in the story. Is it more of a crime to steal a wolf out of someone’s backyard than it is to steal it out of a zoo? Are wolves, like pets, like wives used to be, considered valuable chattel?

Are captive wolves considered property? Or, if: it is illegal to keep a wolf, and someone steals it, in the childlike system of karma and retribution some people in this book have, then 2 wrongs make a right.

• Include scenes on how Hal convinces people to part with a wolf. Include his sayings: Overwhelm the underwhelming. And: In nature there are no excuses.

2

His name was Hal. Hal McGeffer, Rena thought she heard, or Hal McFluggin, or something. She wasn’t sure. It wasn’t that he’d mumbled it, but her ears were ringing. And her hands, apparently, were shaking: they seemed to be holding the keys, though she hadn’t remembered taking them. The keys, plural: there was the truck key, then the other keys, to the house, to the car, to the storage unit, and some old keys from years ago she’d never cleaned off the ring. But when she gave the keys to Hal to try and move the truck, she dropped them all instead, and they splayed out in all directions in the macadam, making a sad metallic thunk.

“Oh,” Rena said.

Hal leaned over and picked them up. “Got it,” he said.

The snow had stopped, except one or two flakes. A stray snowflake fell on Hal’s head as he stood up, silvery, anointed.

“I’m good,” he said, meaning he had them, as she was still standing there, frozen.

“Yes,” she said. “Hal. Thanks, Hal. Saying his name had an underlining feel to it. Like: you really do exist, we really are here. I said your name. That proves it.

“Hal,” she said again, but he was heading to start the truck.

The truck made a coughing sound, a rolling over then coughing again sound, and a choking sound, nearly wet, guttural. She thought she heard Hal grunt or yell something, and the engine coughed again, and then it was running, it was on. “Woo-hoo!” Rena yelled in the giant night around them, the hushed mountains on each side. She felt silly instantly. And as he turned the truck towards the shoulder there was a terrible dragging sound, and the front wheels held fast against the wheel well and stuck. Rena thought of a ferris wheel loose and crooked in its hub, all those tiny people marooned up there in the air.

When Hal cut the engine the night went even quieter. He got out, the door creaking, groaning badly.

“It’s bad,” Rena said, “right?” as he walked back. He had a slight limp. He had long legs. He had long arms.

“Axle’s busted,” he said. He was eyeing the truck as if it were a failed project. He shone his flashlight on it, the mashed in, crooked grille, the hobo smile. “That’s a pretty old truck,” he said. “That truck needed some attention a while back.”

“I know what you mean,” Rena said.

Hal looked at her.

“1992,” Rena said. “It was just meant to be a get to town truck. A beater.”

“Beat is right,” Hal said. “Axle’s broke. Maybe frame. If frame, maybe radiator. Maybe engine. Maybe everything.”

“Hitting the deer did all that? Poor deer.”

The deer was, presumably, still laying between the guardrail and the shoulder, still—still.

“Your truck was already long on its way to truck heaven before this,” Hal said. “The deer maybe just hastened the journey. You could’ve just hit a rock instead.”

“Guess you never know,” Rena said.

“I guess,” Hal said.

It was clear that this was a man from a world where everything to know about a truck was known at all times.

“It’s not my truck,” Rena said. And then: “Well, it is, in the sense that I bought it, but someone else was in—actually, or supposed to be—in charge of it.”

Hal didn’t say anything, but nodded in a two-and-two together kind of way. The clouds had parted and there was a weakish moonlight over them now—which Rena thought, as she looked, didn’t cast shadows. The moon didn’t cast any shadows. Hal flicked his flashlight towards the truck again, still busted up, then back along the guardrail to the deer, still lying on its side along the shoulder.

“I’ll have someone come and get it,” he said.

“The deer?” Rena said.

“Your truck,” he said. “It’s really late. Can’t leave it here. You have somewhere to go? Home?”

“Can’t we help the deer? Oh, god. Not that it has anything to do with this. God. Him or her, or it, I guess.”

“Are you always this way?” he said.

“Only when I hit a deer as I’m running away from home,” she said.

He got on the cell phone with that resigned, take charge and go with it way of a person who just got involved in a mess and now had to see it through.

“Just winch it,” he was saying to whoever he’d called, “flatbed it, but easy.”

“Winch the deer?” Rena called at him as he talked. It was a familiar way of talking, she realized, a pattern people could have with each other: the territory always open, even if the other person was on the phone. But here they were, two strangers out in the middle of nowhere, after all. Except not strangers, now.

“You can’t just drag the poor thing onto a flatbed,” Rena said.

“You can’t chain the axle, being that it’s broken,” he said. “If it’s busted in two the chain could slip and your truck will roll right off. Bigger problems will ensue.”

“Oh,” she said.

“I know,” he said. “I was not, however, referring to the deer.”

She wanted to say, you must think I’m an idiot. But she didn’t.

“I don’t,” he said.

He’d somehow gotten her to wear his jacket, as hers was heaped in with the tumble of all sorts of other things back in her truck, and now she stood in the shoulder of the road watching him work, feeling very small under the weight of this old woolly thing. The coat smelled like animals, like woodsmoke, like meat. She let it weigh down on her shoulders, pulled it close. The night was getting frosty cold, breath white against the dark. But the cold felt far away, as if around her there was a field, a barrier. There were certain things that skittered around without really landing, like when he asked her if she wanted some coffee from his thermos, or was she hungry—she couldn’t think if she was or not, or if she was cold. But the coat felt good. She wondered if the deer was cold. Or if it had a thick coat for winter, and if that had somehow padded it—saved it—

Moving the deer into the back of his truck involved wrapping it like a bundle, hooking it within piles of blankets into a winch, and pulling a ramp out of the bed of the truck, and slowly, carefully, pulling the entire bundle up into the bed. The deer was out of it but not bleeding. Just calm, oddly calm. Even when Hal lifted it by the legs and rolled a blanket under it, it stayed limp, quiet, compliant, unwild, its legs spindling out from its box of a body, its neck concaving back, its tongue impossibly long, resting on the gravel, its eyes open in a flat stare.

Defeated. Resigned.

“I ruined it,” Rena said. “I broke it. I broke its spirit. The deer is acting like it’s already dead.”

“Can you hold this?” Hal said as he worked.

He held out a length of rope, which she took and held, and then he took it back. Rena couldn’t really watch what he was doing. She looked up into the answerless big sky.

“So it’s dead then. I killed it. I knew it. The waste.”

“No,” Hal said. “Just—stand there, all right?”

“Don’t cry,” he said after a moment, when he didn’t hear a response from her. She stood behind him, chewing on the inside of her lip.

“Nature sucks,” she said.

“Sometimes,” Hal said. “Or it just does what it does.”

“We suck,” she said. “Look what I did. It’s in shock, on its way out. It’s giving up.”

“Just be quiet, all right?”

“Is it dead then? I mean you said it wasn’t, but—”

“Maybe go sit in my truck.”

“Okay,” Rena said, “I mean no.”

“It’s resting,” he said. He pulled a syringe out of his pocket and held it up to show her. “Which means it’s dosed.”

“Resting,” she said.

“You never deal with an animal like this if it’s not subdued. Sedated. Tranked. It could kill you.”

“Course,” she said. “How could I not know to just grab the tranquilizer next time—”

Another look from Hal.

“Maybe I should have some of that,” she said.

Hal kept moving, kept working to strap the deer into the bed of the truck, make sure there was nothing hard near it, nothing to hurt it, kept talking to it in a soft kind of monotone, a lilting, subdued voice. He was doing the whole thing in one continuous motion from beginning to end. Rena stopped talking and watched him work, how he focused only on the deer, one hand on its neck, the other working the winch. The winch cable rolled back in slowly, obediently, with nearly no noise. The rope went taut.

“Good,” he said, “it’s taunt.”

“Taunt,” she repeated, but quietly. She was sure that’s what he said. But she had the sense that if she wasn’t careful, somehow careful—careful to not tread on the natural order of things any more, not to trespass, something, she didn’t know, but she felt like if she wasn’t somehow watching her step this night was going to close in on her, the deer would die. The darkness that circled and arched over them, the incredible darkness only yards away from Hal’s floodlight and her broken truck’s already fading, dimming headlights, it would be right there. She was sure.

“You with me?” Hal said.

“Me or the deer?”

“Both,” he said. See?

The deer was donuted into the truck bed, surrounded by a round of blankets and padding. Hal pulled a mesh tarp over the top of it, all the way across to the edges of the truck, and snapped the tarp neatly into the corners. Above the tarp he laid a net that looked military issue: wide webbing straps, interwoven and reinforced. Everything had a gleam and a crispness to it in the glare of his flood light, which he’d set up on the hood of her truck. It was remarkable. Everything fit. It was a system, as if he had done this countless times. It made Rena feel better. A very simple thing to realize—that she felt better. And she then realized on top of that that she was better, at least better enough to realize that she felt better. An accordion, folding and unfolding as she went along.

“How long?” she said. She knew he’d understand what she meant.

“Six hours usually,” he said.

“And you just happen to have that in your pocket,” she said.

“Long story,” he said.

In the dark cab of Hal’s truck she could feel shapes, blankets, clothes. It had a dank smell, a smoky smell, and that same meaty smell, and something that smelled like an old sweater you’d find in a trunk in the attic. Hal sat behind his wheel, looking at Rena’s truck sitting ruined in the headlight beams. “Too bad,” he said as he started up his own truck with a healthy, smooth, throttled roar. It sounded like the engine was enormous, endless. He eased off the shoulder and wheeled around, one hand palming the steering wheel as the other slowly unscrewed the cup off an old thermos clamped between his legs, hooked the cup into the thumb and forefinger of his driving hand, then unscrewed the top, tucked that into his other palm, and then poured the coffee without looking and without spilling a drop.

Rena inhaled the scent, sugary on the edges. It smelled like morning, somehow, though it was pitch black beyond the scope of the headlights.

“Coffee,” she said.

“My blood,” he said. He sipped, purposefully. Rena sat there, next to him, in his coat, aware of the deer in the back—a live thing, the way she’d changed its life, the way everything seemed to be changing. There was such a giant now what to everything she didn’t even want to think about it. But it was beginning to creep back, the sigh of the piles of fruit, the dark fruit, the oozing cheese, the oozing husband, the girl.

“So,” Hal said. “Now what?”

“Afraid you were going to say that,” Rena said.

He told her they’d take the truck to his brother’s, who was a mechanic, who was pretty good with axles and things like that, and he mentioned there was some jerky in the cooler at her feet, and some chewing gum in the dash, and a jug of water under the seat, and did she need to call anyone, and he might have said that a few times. But she just wanted to sit there, not moving, in motion in the dark, not thinking. And she wanted to sleep. But she felt like she had all these things to say. She said, “Nature is so out of whack.” She said, “I didn’t want to hit the deer. The deer, actually, kind of hit me.” She said, “why would a deer run into a car?” She almost said, if you knew what I was dealing with. But she didn’t. It didn’t fit here, all of that. And there was something to that. A mossy thought, but maybe the beginning of something.

“It’s hunting season,” Hal said. “They freak.”

“Hey,” Rena said. “Put your gun down. Don’t freak out the deer.”

“Something like that,” Hal said.

“But I’m pretty sure it ran straight into my truck.”

“The trajectory of the deer is an innocent trajectory,” Hal said. “It is oblivious. That deer is not a car savvy deer. A deer on the run is not car savvy. A deer on the highway is fear on the hoof.”

“Nature is so out of balance,” she said.

“Yup,” Hal said.

[notes:

Wolf hair is thicker than dog hair. The first page of sites relating to wolf hair on google are about hair transplant for men and an eighties haircut that made you look like a werewolf. Then a site about microscopic imaging that contains a microscopic slide of timber wolf hair. But the explanation is only a general explanation about wolves. It has a wickedpedia quality: truncated, abrupt, generic, sweeping but without depth. The words eradicated and reduced and human encroachment are in the description. When the words eradicated and reduced are no longer part of a passage on the clinical content of wolf hair, perhaps certain people will not call me a woman writer anymore. A woman this. A woman that. A condition imposed becomes an unattachable adjective for the subject it is imposed upon.

Don’t forget me, the wolf howled into the wolf-less night from a backyard in New Jersey.

Yes. Nature is so out of balance. Rena can say that because she believes it and she is saying it in part as an offering to the man helping her, who seems hewn from nature, hewn from balance. And because that night, it is. The husband, the girl, the wife. Nature as biology, biology as fielty, but maybe it’s not.

Is she right? Is it that nature is really the great blade of the cosmic knife? In people, driven to the edge? And is that interesting, or just sad? And it is county jail sad or bottle of whiskey sad or grand gestures at the unmoved sky sad or wounded bird sad or it shopping mall sad?

Rena doesn’t really know what nature—Nature—is.

Yet.

The tale-teller’s great mechanism: the mechanism of yet.

So long as you answer the question: when? And not just with later. Or maybe with never. When? Never. That’s the thing.

Later Rena and Hall will have the same conversation. She will say, Nature is so out of whack. She says whack now, because she’s been with Hal some months, has slacked off, that way the brain has of relaxing in its way it says the same thing with a different flavor. More salt, less years in school.

But this time Hal’s bitterness comes out. He agrees with her. But he is the one who’s more formal about it, more pointed. He will say, It’s true. Not enough people dying.

He will startle her, just enough to startle her, not enough to stick.

—And why are we still with them in the truck? Because there is more to know.]

[still 2. See notes, above]

“So where’s home for you,” Hal said as he drove.

“No home,” Rena said. It was a categorical wipeout, she realized as she said it. She had just negated the last seven years of her life in one fell swoop. One swell foop, she thought. She giggled at that. A terrible habit.

“Glad you found something to laugh about,” Hal said, kind of politely.

“I haven’t seen one single car,” Rena said. “Is that usual?”

“Usual normal,” Hal said.

“Good,” Rena said. She thought about what could happen—her husband following her, his white, pale face—ashen, one might say if sympathetic, which she absolutely wasn’t—and the untroubled face of the Philadelphia girl sitting in the passenger seat, the terrible interchangeable apparatus of man/woman/front seat. And yet, he’d tell her if he got the chance, he was chasing after her to get her back, to bring her home, for she was his wife – all that. Because the truth was, it had happened before. You’re my wife he’d said to her once, when she’d run, bolted, wound up at her parents—a mistake, they were traitors to her cause, they didn’t know. You’re my wife, he said. You belong with me. In our home. Our home. The worlds were wrapping paper around a lump of coal. She’d gone back.

She’d left her cell phone in the truck.

Shit, she thought. Then she realized: it was better.

More likely he’d be calling, calling, calling—making the girl feel bad, so bad for him, so sorry for him, for having this overemotional fickle heartless nutjob for a wife—

“I have to take you somewhere,” said Hal. They’d stopped. He was standing next to her window, she’d heard the tick tick of the gas pump as he filled up the tank. The lights of the gas station were weird, silvery, yellowish. Beyond them was still the black night, still endless.

“I don’t know,” she said as he got back in the truck.

“I need sleep,” he said.

She looked at him.

“Well how about a motel then,” he said.

She looked at him again.

“No,” he said. “Not me.” He shook his head. “You. You have to get some sleep. You’re really pale. Maybe your people can come get you in the morning but I have all these wolves to feed in a few hours.”

“Wolves to feed?”

“Mouths to feed,” he said. “Mouths.”

She looked around her, looked around the cab as he started up the truck. The little space was now lit up under the lights. Her feet were resting on the top of a cooler. Next to her, stuck in the molded pocket of the door, was a thick coil of rope. On the dash was a plastic bag with something dark and meatlike in it. Next to Hal—between them really—was another cooler, and jammed between that cooler and the seat behind it was some kind of net, and now she could see that in nearly every nook and cranny was some kind of flannel or blanket, and a piece of what looked like deerhide hung down next to the steering wheel. Beneath that, half hidden, was some sort of radio console with a bunch of phones, or radios, stuck into different slots. And behind her was a gun rack with a rifle in it and a scope. Everything looked kind of dingy, like it had been in something’s mouth. She rubbed her hand on the seat and off came bristly hairs—white ones, and grit, something sandy.

“Mouths,” she said, as they pulled out of the gas station. “So you have a lot of kids?”

“Hm? Me? No, no not kids,” Hal said.

“Dogs, then.”

“You could call them that,” he said.

“Animals,” she said. “You do something with animals. So that’s why you knew what to do with the deer.”

“We’re taking it to the deer lady,” he said. “The rehabber. I’ll have to get up to do that too.”

“Rehab,” Rena repeated. “Drunk dogs.”

He laughed, just a little. He was tapping his lip, in his own thoughts on this wacky night. So this is someone whose worldview, maybe, doesn’t change all that much, Rena thought. It was the kind of calm, lucid thinking a person does when the fire has gone out and the world has stopped turning and the great open sky of the future begins to clear, she thought. As in, there’s a whole world out there, outside of the one that nearly swallowed me whole. And how about that.

“Motel’s another 20 miles south,” Hal said.

“You know,” she said. “You know I really, really would prefer to not go south if it was possible, you know?”

His eyebrow rose up, gave her a look. “We’ve been going south all this time,” he said. “We are.”

They drove the rest of the way in silence. Rena’s shoulders ached. It wasn’t an accident-ouch kind of ache. It was exhaustion. It was seven years. Part of her still wanted to talk and tell him everything, just because it wanted to be told, to be expunged, to be purged, but there was another part of her that didn’t want anyone to ever know anything, that didn’t even want to know herself. And maybe he didn’t want to know, this dog guy. Maybe the rehab lady was his girlfriend, and Rena was just so out of it she didn’t know anything about anyone.

Well she didn’t, did she.

The truck eased off the road, rattled down a bumpy somewhere, then eased onto the road again.

“Shortcut,” Hal said. He pulled into what seemed to Rena like a giant asphalt field. On one side was a long building that had a bear sign and the word NVIEW under it. On the other side was a long building that said OTEL and VACANCY.

“I know them,” Hal said.

The bear sign, propped up on a pole, was turning very slowly. As they sat there, the bear turned a quarter turn. Rena sat, thinking she’d wait for the bear to come back around again.

“So?” Hal said.

She nodded.

It was quiet, that hushed, deep in the middle of the night when people are sleeping quiet. Hal walked over to the office and knocked on the window. In a few moments, a light went on and a woman in a coat came to the door. She looked toward the truck, then patted Hal on the shoulder. There was some kind of transaction. And then it was set.

“Friend?” Rena said when he got in the truck.

“Family,” he said.

“Same family that’s fixing my truck?”

“Same.”

“Big family,” she said.

The gravel crunched comfortingly as he drove behind the long, brick flank of the restaurant. “It’s up there,” he said. “Room 10. I’ll be by in the morning.”

He reached behind her and threw a paper bag in her lap.

“Your stuff,” he said. “At least everything I could grab from your truck.”

There is that saying—sleep the sleep of the dead, and Rena might say she slept that way. Just walked into the room, which was neutral and bare and warm, and lay down on the bed and felt as if she were floating on a raft, somewhere far out to sea, where no one could find her, under the blinking stars. And she woke up still feeling adrift, but wonderfully so—really, it was delicious being nowhere. And then came the rush back: who did she have to tell that she’d left, and had he tried to call, and should she call him, and then the girl from Philadelphia. And the fact that she knew.

She was done. She knew it. She never wanted to go back. She’d rather be nowhere than there.

[notes:

There are all sorts of things going on behind the scenes as she rests, honestly rests for the first time in a thousand years it feels like, in her motel room. And for two days she eats nothing but blueberry pancakes at the diner across the parking lot. And she talks to the waitress and probably says too much, another thing that will come up later. What happens when you talk too much.

The woman who picks up Rena’s truck is a native American [Mohawk] named Trudy who looks like a man from a distance with very broad shoulders and narrow hips and long silver hair. She drives a truck called Trudy’s Big Red Rig which has a whole system of hydraulics and strapping that can lift up anything, including small houses that do not exceed her 12-foot by 20-foot limit. She says: 12 by 20, that’s my limit. She says it in all sorts of situations, like refusing another plate of steak.

Rena does not know any of this. She never finds out the whole thing, because something else happens that makes—that causes—she and Hal not want to talk about the truck much. But soon, as she meets everyone in the group of people Hal works with, the covert wolf rescuers, she meets Trudy. Trudy is summoned to assist again because the wolves they have to go get are all locked up in a shed. They wrap the long straps around the shed and lift it whole hog onto a flatbed truck, owned by Horace, Hal’s brother. They take the wolves and the shed and drive off into the night.

I know you, Trudy will say to Rena as the shed is being settled into Horace’s truck. You’re the one who hit the deer with that little wrecked up truck that I had to tow to Horace’s garage.

Hal’s brother Horace is usually just called “Hal’s brother” even though he’s the older one. By virtue, or lack of, his making a mess of his life he’s been demoted to younger. Hal, on the other hand, is never called Horace’s brother. Horace sometimes gets drunk and rants about this until someone sends him home. He is famous for driving blasted on Schlitz and never getting in trouble for it. He can gearshift a semi through the worst mountain passes and get it home safe and pass out a minute later and wake up slumped over the wheel, facing his singlewide trailer, having stopped two feet away from the propane tank under the kitchen window, which is where he usually stops.

Horace is a bit of a ladies man. The waitress at the Bear diner often sleeps with Horace. To her girlfriends, giving her shit for sleeping with Horace, she’ll say, it was a sympathy fuck. But Horace gets around. Which of course makes Rena wonder about Hal. If it’s in the blood of one, is it there in the other? Rena has a special talent for second-guessing herself. One night, when they’re on a wolf rescue stakeout, Trudy will try to give Rena some advice. Trudy, who may eat a donut or two too many but at least she doesn’t drink, as she’ll say to Rena. She says to Rena, “You know, sometimes it’s good to shoot first and never ask questions.”

“You mean not ask questions later,” Rena will say, wired from Mountain Dew and no sleep. “You mean shoot first, shoot later, kind of.”

“That,” says Trudy, her lips powdered with sugar. “Sure. That works for me.”

Trudy will also tell her that Hal was actually hoping the deer would die. Because it’s hard to feed this many wolves. And Rena will learn about the road kill posse that travels the highways and back roads just as dawn comes up, looking for road kill, posting their finds on a GPS. Pinpointing the UTM coordinates of a dead raccoon, a bloated woodchuck, a mashed cat. The faster you get there, the more there is to salvage, the more for the wolves.

And Rena will get to know the whole wolf thing intimately, because she has no judgment, she’s just along for the ride, a wideopen eye on the surfboard of life, as Horace tells her. “Captivity’s a bitch,” Hal says to her one day, about three months into her staying at his cabin.

“I know,” she says.

3

After Rena has been staying at the motel for about four days, he appears. Jamie. She is coming back from another breakfast of sausage and blueberry pancakes, and feeling all right, and the door is ajar. She opens it.

There he is. Of course. Everything goes thud. She tastes her breakfast just gone down and makes a quick deal with herself to not be sick.

I mean it, she says to herself. Butter gone sour, maple syrup gone metal.

She swallows.

He is in her motel room. He is sitting on the bed, surrounded by all of her things. Her things are arranged in a circle all around him as if he’s casting a spell. A T-shirt, that bark picture, her house keys, a book, socks, a notebook, her wallet. He is sitting cross-legged, wearing his hoodie, his expensive jeans, his immaculate custom-made boots, sitting smack dab in the middle of her bed.

“Please don’t let my appearance frighten you,” he says. She notices he is wearing his wedding band, something he never did before. He used to keep it in the top drawer of his dresser, next to the condoms he wouldn’t throw out, and his French underwear, and a photo of his mother.

She stands there, in the doorway. Her room is toxic now. She hears buzzing. The radiator, under the window, seems to be smoking. Or it’s just a seeping kind of darkness, invisible smoke hazing over everything.

Whatever it is, she can’t go in. She feels the cold air on her back, a hand, steadying her.

“I knew you were here,” Jamie says after a moment. He picks up the notebook. The notebook is empty. “Empty,” he says. “Not one word.”

Steady.

“I was looking for some sign,” he says, his voice steady and kind of airless. “I was looking for a sign that you still loved me. That you still cared about me. That you wanted us to work. But there’s nothing here.”

Rena thinks, of course. Of course he assumes that the notebook would contain her endless confessions of how much she loves him. His view of the world—in terms of evidence that it adores him, only.

“So I guess you don’t,” he says. “And maybe you never did.”

A stretch, Rena thinks, but says nothing. She lets him unspool.

“And maybe you were lying to me all this time. Seven years you lied to me.”

“Wow,” she says.

“I knew you were here,” he says. “It was so easy. I got a call from the garage that the truck was ready. There is only one garage and only one motel and only one road and it was so easy. I would have thought you’d be in—in Florida by now, or something. If you really wanted to run away. It’s kind of impressive that you stayed so close. It sort of gave me hope for a moment. But when I care here, the room felt so dead. No sign that you cared. It was—it was loveless.”

Rena stands there. For no reason her thumb finds its way into the square where the doorknob’s bolt goes, and it stays there, hiding. The truck has been ready for three days. So for the three last days, while she’d been feeling free, and safe, she really hasn’t been. It’s just that Jamie was busy. He was probably screaming and between screaming, who knows.

“He told me everything,” Jamie says. “Mechanics are so easy. And he said to me, you know what he said? When I told him how you just ran out and left me alone in my own house, he said ‘Man, if she’s your wife, and you want her back, I’d go for it man,’ is what he said. He said that.”

“You weren’t alone,” Rena says. “Bet you didn’t mention that part.”

Jamie’s voice cracks a little, unphased, moving along, telling the tale. “So I did what the mechanic told me,” he says.

Rena wonders if it was Horace, fuckup brother. She wonders if when Horace got a man’s voice on the phone he went, “Oh, sorry, never mind.” And Jamie, being Jamie, just gave a little jerk on the chain until it all came out.

Doesn’t matter now.

“Do you want to close the door?” Jamie says. “It’s so cold out. We haven’t slept.”

“We?”

“Kumi and myself. She’s really insightful, actually. And so supportive. Really mature, you know, well beyond her years. I know you didn’t give her much of a chance. And it seems as clear to her as it does to me that you’re moving on. That you have already moved on. Maybe you’d moved on already. Maybe that’s why you acted that way. Kumi suggested that. But I don’t want to know. But you know how I am. I can’t be alone. I just can’t. It breaks my heart to be alone. It takes my breath. You were my oxygen. I think you truly may have nearly broken my heart.”

He is taking money out of her wallet. She didn’t bring her wallet to breakfast this morning because she just wanted to sit there, no i.d., no nothing, just take a few loose bills out of her back pocket when she was ready to pay, just slip them with the check under the thick white saucer under the coffee cup, the coffee cup that is never empty because it’s always being filled, just feel that free.

“And to think we were talking about children,” Jamie says.

“I need that,” she says. “It’s my money.”

“It’s our money,” Jamie says.

“So take half,” she says—ridiculous, she knows, trying to reason with his nonreason. But there’s the ground, slipping from underneath her feet. The pepper from the sausage is leading the way. False alarm. She bites at her lip. Wants blood. Something alive.

“From what I heard, you don’t need the money anymore,” he says. “But I’ll leave you enough to pay for the truck. Nice work. I had just begun restoring it. You are so—”

“What,” she says, going blind now, the room going red.

“Destructive,” he says. “But I’m free now. So I guess I should thank you.”

“You’re welcome,” Rena says.

4

How she got to Hal’s cabin was a phone call, panic, his just saying I’ll make room, he just coming to get her, they left the truck at his brother’s, she could pick it up whenever after he strangled Horace, he joked, or it wasn’t a joke, and she didn’t really think, she just let the tide carry her, and she grabbed her bag and was waiting in a booth at the diner when he pulled up, with a giant dog that had a head as big as a snow shovel poking out the window.

“Meet Ralph,” he said as she climbed in. The dog was bigger than a Great Dane. It hopped with its giant pony body into the back behind the seats and disappeared under a heap of blankets.

“Whoa. Possibly not a dog,” Rena said.

“No,” Hal said.

Off the main road they drove up a long, long pass that seemed to wind forever, bending into a switchback, then a straight uphill, another curve. They came to a broad plateau, and a drive through some woods, and they came to a clearing, and there was a cabin—plain planks, a tin roof, painted a color that wasn’t red and wasn’t brown and wasn’t orange.

“Home,” Hal said as Ralph that wasn’t a dog jumped out the window and jogged down the hill.

Rena heard yips, a snarl, more yips.

“He’s having a good day,” Hal said. “Some days he can’t hardly move.”

Rena stood there, inhaling the coolness in the air. She was, she figured, about 100 miles north of the mess. A couple thousand feet up.

“Should I explain?” Hal said.

“No,” Rena said. “Not yet.”

Ralph had what looked like a grin on his face. He had yellow fangs that looked about three inches long. Can opener teeth, Hal called them. He came loping around Rena, then stopped, facing her. He was about three feet high at the shoulder. He looked at Hal, then walked, very slowly, but loosely, up to her. He lifted his nose into the air and stood four square, lifting his tail until it was parallel with the ground. He flattened out his head. He took an audible sniff.

Three feet away, Rena smelled his scent: old fur coat, a scrum of musk.

“Mutual check out time,” Hal said.

“Does he like me? “she said.

“I like you,” Hal said. “That’s how it works. I give him meat. I like you. Equals hands-off you, kind of.”

“In his math,” Rena said.

“In wolf math,” Hal said.

Ralph blinked his giant flashlight eyes at her in a way that either seemed very trusting or very calculating.

“I think he likes me,” Rena said. “Can I pet him?”

“We’ll get there,” Hal said.

“Why is his name Ralph?”

“It’s the sound he makes when he’s really happy,” Hal said.

In the olden days the people lived in the valley and the wolves lived up on the ridge around them. They had their dens. They had their packs. They had systems for everything: hunting, breeding, calling each other, telling each other off, eating, sleeping. Then the world turned upside down. And now the wolves filled the bowl of the valley, kept in by miles and miles of fencing, barriers. Hal and a whole lot of other people lived up on the ridge around them in a ring of cabins and campers and prefabs, vans and trucks and chicken coops and cow barns.

“Back in the good old days they outnumbered us,” Hal said. “We had to protect flocks from them. Our cows, our sheep. Now we have to protect them. That’s what we do. I figure I might as well tell you. But it’s not big news. We keep it close to the vest. It’s not common knowledge.”

“It’s covert,” Rena said.

“It’s complicated,” Hal said.

Time: Rena didn’t keep track of it.

They ate as the wolf slept, emanating the scent of old fur and must into the room. Rena could taste it, a musky veneer over the jam on toast.

They all worked together, rescuing wolves. They had a mission statement and a secret members-only website and a benefactor. They had procedures and lots of rules and disguises and fake names. They had generators. Solar panels. They had built their houses on this ridge that encircled the valley, had filled the valley with their rescued wolves and laid acres of camo netting over the bare part of the land to conceal it from anything flying overhead. They had elaborate landscaping to make the valley look like it was chopped into parts. They freed the wolves from backyards, from houses, from country fair wild animal shows, carnivals. From cars and from cities. From puppy mills and pig farms and dog fights and shelters and zoos. Rena had no idea there were so many ways to keep a wolf. When she brought it up, Hal just rolled his eyes. “Humans should not go to heaven with all we do,” he’d say.

5

Overnight, as Rena and Hal slept off dinner and pie and sex, the snow came and went, turning Hal’s yard into a sea of little white hills. In the juvenile pen next to his house, the young wolves chased each other through the stuff, splashing waves of snow and mud above the fence. Rena, still in bed, could hear the thuds as they crashed into the boards, shaking the wall, hear the yips and growls.

They were, said Hal, celebrating. Adults went nuts before they ate, then wisely slept it off. Juveniles romped for hours after a meal, burning it all up. “Still foolish,” Hal said as he skinned off his coveralls, switching to jeans as Rena watched him from under the covers. He’d been up and at it since 5.

He was a rangy 54. Nothing extra. Sinew and bone, strong legs, long arms. Not that young liquid symmetry. More a man making a bargain with himself: keep working, we’ll get to rest someday. Hal’s broad shoulders pitched forward a bit, his arms hung a little inwards. His belly was a little hollow. But he was lovely. And good.

“I want to be foolish,” Rena said, enjoying her morning gander.

“You’re not foolish,” Hal said.

They were brand new lovers paying rapt attention to each other, thinking everything the other was said was clever. There was such intelligence to new courtship, such focus. Rena knew he didn’t understand everything she said but she said whatever she felt like and he listened. She felt dewy and wispy as she snugged the thick covers over her, wanting to stay in his bed, in his house, on top of this big mountain, protected by all these wolves and his gun by the door and the whole clan nearby, all day.

Really, Idiot, her new and only name for he who had become unanameable, could never find her here. He’d never make it up the road. If he did get inside, she imagined, he’d get eaten by Ralph.

“Bacon?” Hal said. “Pancakes?”

Hal had already chainsawed the frozen carcasses for the wolves’ breakfast. She’d heard the ATV start up and head across the yard and then downhill to the big enclosure, heard the whine of the saw, heard the wolves making their mealtime ruckus. She’d pretended to be asleep when he came back inside to kiss her awake, smelled meat and winter and gasoline as he leaned in. Another thing new lovers got to do. Be amazed by each other’s sleeping and waking. And now he was peeling bacon into a pan and scooping coffee into the machine. It felt so good. It felt stolen. It felt deserved. After everything.

“Maybe I’ll ride with you to feed them tomorrow,” she said.

“Tomorrow they don’t eat,” he said. “The only one who eats is Ralph, cause he’s so old.”

Ralph lifted his giant, silver wedge of a head off his bed and licked his lips back at Hal. He’d quietly purloined Hal’s discarded coveralls and now had them pinned under an enormous paw. He mouthed them studying. His bed was a mass of stolen coats, blankets, t-shirts, socks, pillows, whatever he claimed. “Don’t touch it,” Hal had said to Rena that first night, “and don’t stare at him and don’t expect him to make room for you. He’s permanent. And he knows it. And don’t feed him treats or he might decide to try your hand.”

“He’d do that?” Rena said.

“He’s a wolf,” Hal said. “You don’t really know what that means yet, but they play rough.”

Rena decided to hang on the part of the sentence that contained the idea of yet.

But it was a serious thing to Hal. It was the one non-joke, the backbone, the core. The black and white. There were rules and there was no breaking them. Everyone who lived around here was involved, it seemed, though Rena didn’t know exactly how. The woman who’d come and taken the deer away, the deer she’d hit that first night, she was one of them. And Rena knew there was some old lady in Palm Beach who bankrolled it all. And called Hal a lot. And now as the bacon began to sizzle, Ralph the non-dog raised his head, yawned, showing all those long yellow teeth, and gazed up at Rena, the visitor, who weighed less than he did, and stared at her with his amber eyes and rested his chin on the edge of the bed, just a few inches from her leg. He swiveled his triangle ears towards the bacon but he kept his eyes on Rena.

“Does he like me or is this about the bacon?” Rena said.

“Why don’t you go take a shower,” Hal said.

“Hey Ralph,” Hal said to the wolf, as a piece of bacon spun through the air.

“Going to take that shower, right now, would be good,” Hal said to Rena.

It was a one-room cabin, everything against a wall: kitchen stuff, wood stove, battered old couch, bed. It was a mess. There was no use straightening up. Ralph would just rearrange it back to his own liking. Rena kept her bag on a hook up high on the wall.

The shower stall was made of tin and banged loudly when she hit it with her elbows every other second. But she took her time, letting the room steam up as she reveled in the heat. At some point there’d been a woman around: the walls were painted peach and there were fussy pink towels with flowers. Rena found some old herbal shampoo under the sink, a bar of Olay. The soap was dusty. The shampoo had crust on the lip. It had been a while, whoever she was.

“Hey beautiful,” Hal said when she came out, swathed in towels. “Come eat.”

Men don’t say that to women they live with, Rena said, sitting down.

“I do,” Hal said.

He dished out a pile of fluffy pancakes and poured syrup over them in a sweet, langorous pool. Laid strips of bacon over the top. “There,” he said. “For the record. But don’t tell anyone or the myth will be shattered.”

She ate. More like, she let herself eat. She hadn’t wanted to, for months. She’d whittled herself down as if trying to make herself thin enough to slip through a crack, to disappear. And now that she finally had, she was famished.

“More,” Hal said, forking over bacon. “You need it.”

She ate avidly. She ate dreamily. She kept half an eye on Ralph, who was curled up and snoring in his nest.

“So you’ll come with me to this thing today? You can meet them,” Hal said.

Somewhere 100 miles to the south Idiot was filling their house with screaming and downing bottles of Chilean wine. She could picture it, he in his hoodie and sweatsocks, rubbing himself in agony as Kumi watched, blank. Probably bored. Bored by now.

But Hal’s coffee was rotgut strong, a little gamy, a flash of light to shoot Rena into the day laced with sugar, and his hand was sweet on her hair and she shut out the picture.

“I kind of feel like just staying put,” Rena said. “Would that be okay? Just not face so many faces? Do you know what I mean? Just, kind of, that much?”

“I know,” Hal said.

[notes:

“Captivity’s a bitch,” Hal says, watching a young wolf pace the enclosure, eyes flat. “Thing is there’s a hundred acres for the wolf and he still thinks he’s in someone’s backyard.” The wolf paces the length of the backyard, turns back, paces the length of the backyard the other way, turns back. “His brain is fried at 200 feet,” Hal says. “I saw him pacing exact same way in the video the people had put online. Like some kind of brag.”

“People are disgusting,” he says, as he throws the wolf a hunk of cow leg, out of the range of 200 feet, and the wolf ambles towards it, then stops, frozen at the edge of his 200 feet.

Backstory: the video is how they got this wolf. The benefactor saw it, actually. She has a habit, down there in Palm Beach, within the hush of the central AC, of putting on Perry Como and trolling online, drinking a wine spritzer out of a Waterford crystal goblet, looking for wolves. It moves her. She has to do something, she has to feel like she’s doing something for them. And that’s how it works.

“How much did you pay for this one?” Rena says. It’s March and cold. The ground is a rolling mess of dirt and ice and wolf shit along the fence. Freezing rain has coated all the roads. Horace is getting around in an old Pontiac with tire chains, road kill and cow parts loaded in the trunk, the backseat.

“This one cost $75,” Hal says to Rena as they watch the wolf lean, carefully, as if an electric shock is going to come next, and then take a step towards the hunk of leg that came with Horace this morning.

Horace is in Hal’s house, sleeping it off. Ralph, Hal’s wolf, loves Horace. He loves Horace like a brother. Together they roll and moan in brotherly ways. They smell about the same these days, since Horace is single again.

Some wolves are free. Some wolves are part of giant package deals that involve money orders and bank transfers. Most are cash exchanges, usually after a few tries. More on that later.

On the cow leg is the fragment of a number tattoo, Rena sees. The chainsaw split it in two.

“Not very much,” Rena says. “75.”

“I made them sell it,” Hal says. “I told them the chances of his living were about 40 percent, which meant there was a good chance that in disposing of his body someone would find out, which meant there was maybe a ten percent chance they would be arrested, but that 8 times out of 10, it gets written up as a felony misdemeanor, and if they have children, which I’m sure they do because I heard a little voice in the video squeak, ‘Make him mad, Daddy, I want to see it,’ if they have children it can trigger a child services visit. And also that wolf pelts, since they’re so easily gotten in other places, are not worth all that much. Maybe 5 bucks. So my deal was the best deal they were going to get.”

You said all that?

“Overwhelm the underwhelming,” says Hal.

He watches the wolf. It’s so cold and damp out that Rena’s hands feel like they’re turning to ice from the inside out, bones freezing first, then skin. “He won’t eat it,” Hal says after a long minute. He needs something live.”

Those things that Hal says that Rena notes: The overwhelm the underwhelming thing. The nature and excuses thing. Let’s not get overethical here. Wolf wants tomato soup, wolf gets himself tomato soup. Can I toast your bread, honey pie? Truck’s not running right. Needs some protein. My brother’s in woman trouble again. What else is old. I don’t really know much about where you came from, no. Do I have to? Humans do not deserve to go to heaven. Not with what they do. (and variations) I’m going to let it out when I’m not looking. Time to ram a 22 in his ear and make him listen. Next man who gasses a wolf den gets strung up by his manicles. That wolf forgot it was a wolf. It needs to kill something. And once, after a disturbing phone call: How about your ex husband?

Jana Martin is the author of Russian Lover and Other Stories. She's been with and in Spork for a long time now, and this bio is a placeholder that'll appear only in the first couple batches of issue 9.1