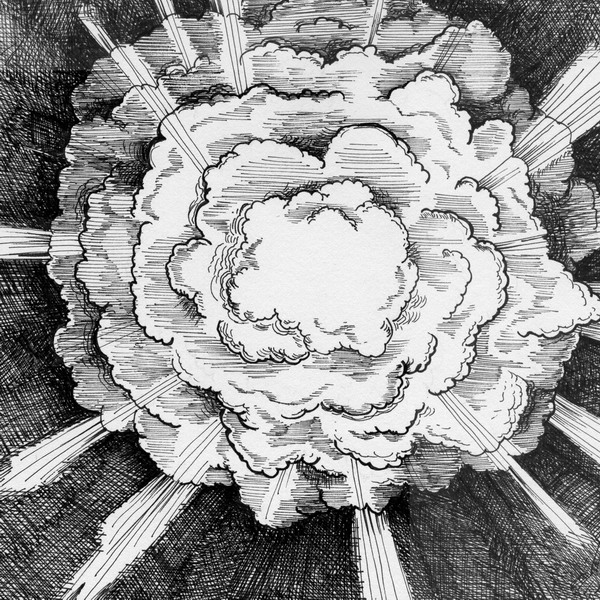

at her when the Reality Engine exploded. Spandex-covered arms and legs flew everywhere, bloody fountains shooting up to the sky. Major Man’s head bounced on top of a police car. Wondra’s dead body smashed into the pavement. Darkness’s bloody corpse fell in pieces beside it. We stared at the mess, waiting for a survivor to walk out, but if Major Man was dead, that was it. No one was walking out. No more superheroes. All gone.

I looked at Selma because I thought she’d love me again, but she was holding Keith’s hand.

Lenny pulled a joint out of his ridiculous Jew-fro, one of the infinite number of joints that must have grown in there from seeds and twigs, and he dropped it on the ground without ever looking at it. He grabbed another out and I took that one and lit it and then we looked at all the cops and the crowd and the blood and the dead, all of them dead, and we ran off into the woods again.

Lenny pulled a joint out of his ridiculous Jew-fro, one of the infinite number of joints that must have grown in there from seeds and twigs, and he dropped it on the ground without ever looking at it. He grabbed another out and I took that one and lit it and then we looked at all the cops and the crowd and the blood and the dead, all of them dead, and we ran off into the woods again.

The stars were dipping and swirling in the sky and Conrad said that he was all out of mushrooms which I was glad for because I could hardly handle the ones I’d already taken. Lenny put his hand on my shoulder and said “I didn’t think we could be friends but I think we’re friends,” which is the kind of shit he always said when tripping, and I threw up. PCP in the pot.

Selma was resting her greasy head against Keith’s shoulder. What the fuck, Keith could have anyone he wanted with that chin of his. I puked again. “I’m glad we’re friends,” said Lenny, and I think I passed out on the plywood floor of the fort, but I don’t know, maybe I just woke up there.

It was still dark and my head hurt so bad. I reached behind it and my hair was matted with dried blood. I felt around and my finger slid into a long trench on the back of my skull, like the skin had been split and folded over on itself.

“Keith!” I whisper-shouted while opening his eyes with my fingers. “Keith!”

Selma moved her greasy head against him and I could see the pimply tops of her breasts loose in her tank top, Keith’s hand stuck inside auto-tweezing her nipple.

“Wha?”

“Keith! Somebody bashed me in the back of the head.”

“Who?”

“I dunno. A bad man.”

“You’re wasted. Go back to sleep.”

I grabbed his hand and stuck it in the wound.

“Shit! Fucking shit!” he said, like I didn’t know.

“Shh!” I said, “You’ll wake everybody!” though there was little chance of that.

We walked down the dark trail to the road and hitched a ride to the hospital, which was maybe a bad idea, tons of people from the exploding Reality Engine there for trauma or something. I mean, no one was really hurt, and because I had a wound I eventually got to the front of the line. They sent me to a doctor who smelled like an old lady.

“You been smoking grass, son?” he asked. I probably reeked.

“No, just had some beers.”

He yanked on my hair to get the two sides of the wound to line up.

“You sure you didn’t have some grass?”

“Can you fix my head?”

“Yeah, you don’t mind if you have a scar, do you?”

Of course I didn’t mind. Selma had a scar. Scars make you more interesting to look at.

The next day the paper was all about the explosion, and yeah they were all dead, and blah blah blah. I think there was going to be a memorial or something. I can’t believe they picked our town to do it in. Center of the world, edge of Connecticut.

I sat on the floor of my bedroom and read comic books like I used to do when I was a virgin, and I remembered when Keith and I spent three days in the woods with BB guns shooting at each other and eating dried soup and stream water. One of them flew over head, not sure which one, but he had a cape, and we took shots at him, not because we thought we could hurt him, it’s just, we had the BB guns, you know? Then we shot each other at point blank range. It hurt a little, but the BBs mostly bounced off our clothes. That’s how it seemed like it was going to be here, always and forever: no one was going to die or get shot, nothing was going to happen.

After the doctor sewed my head up we went back to the fort and Keith immediately got so high he passed out. My head hurt and I didn’t want to smoke any more pot so I tried to remember when I was a kid and did gymnastics and thought completely different thoughts. Like, instead of thinking of overcoming death through eliminating the ego, I’d think: who would win in a fight between God and Captain Invincible? And I realized, these are really the same kinds of thoughts. Stupid shit that doesn’t matter about made-up things.

What I needed to think about was: who bashed me in the back of the head? It couldn’t have been Lenny or Keith or Selma. Conrad? He was an asshole but not the violent type, more the type who’ll steal your pot or tell people if he saw you jerking off. “Fuck this,” I said, and walked down one of the trails. Lenny wanted to follow me but I’d had enough of him. I was only friends with him because Keith was and I have no idea why Keith was friends with such an idiot except that Lenny had lots of money and drugs.

I walked through one of the many old graveyards that you’d find in these woods, and towards some church walls that still stood two storeys tall with no insides and no roof and lots of little trees growing between them. I climbed up to one of the windows and sat inside it. “You should have been there.”

Who the fuck said that? “You should have been there,” it said again, and then I heard a scampering in the woods, like a deer, and saw some bushes rustle. Fuck. Somebody knew, but they were all dead. I pulled the tiny mask out of my pocket and fingered it. If they’re all dead we’re probably safer anyway.

It was one of the rare nights when my father was home and not out on some business trip picking up herpes from 50-year-old bar tramps. So of course I had to have dinner with them, with my family, no matter how little they liked me or how much I didn’t care about them. There were chunks of steak, I guess, but they were burnt on the outside and raw on the inside. If my mother was a drunk I could at least blame that for her terrible cooking. In fact, she did it because she was mad at my dad, and this was the best way she could think of to express it: giving her kids e. coli infections.

Normally we’d have the following conversation:

“What did you do today?” my dad would ask. All day today I did not fuck wrinkly old whores with venereal diseases, dad!

“Nothing,” I’d say.

“Nothing?” He’d sound mad, like I was lying. But really, what did I do in the last three years that I could tell him about? What did I do in the previous three years that I could tell him about?

But tonight he wore the look of concern that businessmen keep handy for when they’re supposed to have been affected by something. He lit a cigarette in the middle of the meal. My mother was probably furious, which she expressed by swallowing once or twice a little too loudly.

“So,” said dad, acting like he was going to make a Big Man speech. “After today’s events, I’m just glad we’re all here, and safe, together.”

Wow. That was it? I hope he didn’t rehearse that.

My older brother looked down at his food. Someday, he’d probably try to kill my dad, because he cared about things like family. Let it go, Timmy, let it go!

My sister looked up anxiously. I tried to swallow a raw/burnt piece of meat, and started to gag. I pointed to my throat, and stood up. I was actually choking now, and I went out of the room to vomit.

When I came back, luckily, the meal had ended. I grabbed a piece of bread and went up to my room.

None of my friends called me that night. Did they ever call me, or did I always call them? They were probably out in the woods again getting high. I stayed in my room and didn’t smoke any pot until it was just about time for me to go to sleep, blowing the smoke out the bathroom window. In this life I was a coward. I think it happened when I took all those mushrooms and forgot my name. I hadn’t felt entirely well since then, what, a year ago? Two years after I quit. Why would you be a hero in Connecticut? The only crime here was teens like me buying cocaine from middle-aged fags and then staying up all night talking about reincarnation and God.

The next morning I called Keith. One more month of summer then we’d go to separate states to study. He was going to art school in Rhode Island. When did he stop liking me?

“Keith, what’s up?”

“Nothing.”

“What you doing?”

“Nothing. I’m doing nothing.”

“Not doing anything?”

“No, I’m doing nothing. You wouldn’t understand.”

“Is Selma there?”

Keith didn’t say anything. “Is Selma there?” I asked again. He still didn’t say anything. The phone wasn’t dead. I could hear him breathing. “Keith?” Nothing.

I got in my mom’s station wagon and drove to his house. The door was open and his two little brothers were lolling in front of the TV. Keith was sitting in his room in the lotus position, eyes closed, palms upward on his knees.

“Keith!”

He didn’t say anything.

“Keith, why didn’t you answer me on the phone?”

“I didn’t feel like it.”

I stared at him. He was really pretty for a boy. There were so many people who had a thing for him, we used to call them “Keithosexuals.” It didn’t matter if they were male or female, they wanted Keith, and he and I had been best friends.

One time Keith asked me if I wanted to have sex with him and I laughed in his face and said “No!” I guess that was an opportunity a lot of people wouldn’t have passed up.

“Do you want to go, umm...do you want to...” What was I going to say? There was nothing to do in this town but talk and walk, and Keith was done talking to me. My head hurt where the wound was and the stitches itched. Who the fuck smashed me in the back of the head?

Keith opened one of his eyes. “I’m connected to my own death,” he said. It was shit like that that made people love him. People who didn’t know him well enough.

“Me too,” I said, and walked down the stairs. Keith’s mother stopped me. “Can you take the twins up to bed?” she said. Keith’s little brothers were asleep in the living room. “Sure,” I said, and picked one of them up to carry him upstairs. Even though Keith’ mom put away a half bottle of bourbon a night, I liked her. I think any mom is better than your own mom. Probably as she watched me carry her youngest kids up to bed she thought the same thing about sons. She gave me a kiss on the cheek and I went home to my room to jerk off.

That morning I was having a dream of a giant man with wings saying “Then. Then! THEN!” I woke up in that hard way you do when you haven’t gotten high in 18 hours. Then what? Then what the fuck? Then why the fuck bother? I was oily with sweat, still in my jeans and t-shirt.

I changed my clothes, grabbing an old T-shirt that Selma had left at my house months ago. It had a little hole where her nipple would sometimes stick through. I remember talking to her about the heroes and she told me that the encouragement of non-compensated vigilantes was a boon to the state because they acted outside the constraints of the law and required no governmental funding. So if you wanted to intimidate and harass people who don’t pay taxes without raising taxes on those who do, vigilantes were a smart move. Selma used to be concerned about real stuff like that before she hooked up with Keith and switched to talking about perception and reality and all that spiritual bullshit.

That political stuff she said, though, it worried me in a way the mystical stuff never could. It was like she was saying that everything that everyone though was good was actually a conspiracy against the poor. Old ladies who were rescued from supervillains and went on to own their own homes were just benefitting from an infrastructure built by slavery and oppression. Fuck. I didn’t want to believe that, but how could I not believe the first girl to ever touch my dick?

That night I was hanging with Lenny because I couldn’t find Keith. He was probably fucking Selma. Lenny was an idiot, but as a result of that he was always available.

“Lenny, look at the back of my head.”

“What?”

“Look at the back of my head.”

“Ok.” Lenny stared dumbly at the back of my head. “What?”

“The scar? The, the, I dunno, the dent in the back of my head?”

“Yeah?”

“What’s it look like?”

“It looks like somebody hit you with a two-by-four.”

How the fuck would he know the dimensions of the wood that hit me? Did Lenny hit me?

“Did you hit me with a two-by-four?”

“No! No! Fuck no! What the fuck!?” I turned around and Lenny looked all betrayed. I guess I knew how that felt.

“Ok, sorry, forget it. I probably got up and then fell and then lay back down in the exact spot where I was sleeping before. Whatever.”

Lenny looked a little scared and jumpy, like I was gonna leave him for a better stoner. I reached into his hair and pulled out a joint. He smiled and we lit it up and then ran off down the trail to where the rope swing was. We spent the next hour flying out over the lake and diving in until a copperhead snake swam by and then we ran off. I felt weird, like I was having a good time while I was waiting to be punished. Or maybe like the little kid-me was laughing and playing and the grown-up me was getting ready to puke from the anxiety and the shit I had to tolerate. Fucking Selma and Keith. Fucking dead heroes. Fucking mask in my pocket.

Here are six things that are more fun while high:

1. Walking in the woods

2. Talking about God

3. Sitting and staring into space

4. Climbing a water tower

5. Eating

6. Everything

Actually, no. Nothing. Once Selma and Keith and I went to New York and bought some pot. We smoked it while crouching in a small traffic island surrounded by hedges, and it turned out it was laced with PCP. We couldn’t leave that little traffic island for two hours. Two hours, hiding behind a hedge, surrounded by cars, wasted out of our minds, waiting to go home.

I have no sympathy for me now.

That night I went out to the fort by myself, parked the car at the end of the trail and walked up the woods in the moonlight. Whatever skittered by in the corner of my eye wasn’t a spirit or ghost or my personal avatar of death telling me I’d survive. It was just squirrels, I decided. I was going to believe normal things today. I was going to believe that when I got to the fort that my friends would be there and we’d sit down and talk about God and spiritual power and the path of true seeing, but I wouldn’t buy it. I would only believe normal things.

I saw a small fire on top of the hill. Selma and Keith were stirring the ashes, sitting by the fort with smoke in their hair. I felt like a piece of fruit that had been juiced out.

“Hey,” I said.

They looked up at me blank-eyed. A new secret.

“Hey,” I repeated.

They just stared. Keith held up a piece of paper that said “silence” in beautiful lettering.

Keith and Selma stared right at me. Did you ever have two people stare at you at once, two people who were your best friends, one after another, at some point in the near past? When they do that they are saying: we have a secret. We discovered another great truth while you weren’t here. You can’t see it. It’s not for outsiders. That was true of all the truths, but I used to be an insider.

I sat down in their silence and waited. Then I had an idea. “That’s it!” I shouted, standing up. “Look!” I pointed past the fire. “Did you see it?”

“What?” said Selma. Keith looked angry. I’d gotten her.

I pulled her hand to the back of my head.

“No one hit me,” I said. “Something escaped from within my skull. Feel it. The wound is pushed out from the inside!”

It wasn’t. It was clearly bashed in. But who could feel that now, with the stitches?

“Out?” she said.

Keith couldn’t show that he was bested. I had a secret now.

“It all flows outward,” he said.

“No, you don’t understand!” I said. I thought that was a good move on my part. I couldn’t let him steal the secret. I was still inventing it. “Nothing flows outward, and it was the nothing flowing out of me. The everything tries to flow in, but you can block it by letting the nothing out. That’s what I did. I remember now: I released the nothing.”

Keith stared at me. I had him. That was good material. “I...” he started. His pause was a loss.

“I can tell you how to let the nothing out by opening your head. I did it so forcefully that it manifested as a physical wound, but I learned the silent way of doing it. That’s why I sent you a message of silence,” I said. I might have been overreaching. Could I steal their secret with mine?

“You can’t send a message of silence,” said Keith, “that’s why it’s silence.”

“That’s why I sent it,” I said, “so you’d know that.”

Score. Awesome fucking total score. Selma looked at me, eager for the doctrine. I stood up, arms outstretched, ready to give the doctrine. Something struck me on the back of the head and I was out cold.

Being knocked unconscious is a lot different than it’s portrayed in comic books and movies. First of all, people are rarely knocked unconscious by a single blow to the head. Mostly a single blow to the head just hurts like hell. But if you do it just right, and get lucky, you can knock someone out. The problem is, you’re very likely to have killed them or caused serious brain damage. And even if that doesn’t happen, people don’t just wake up later going “what happened?”

Instead, they wake up with terrible headaches. Far worse than the kind of headaches you got from not being hit on the head until you’re unconscious. This was an important thing for me to learn

I woke up in the darkness with Selma staring down at me. Keith was there too, sitting back a bit. My head really, really hurt. I had been thinking or dreaming all these nasty thoughts about how lame and stupid everyone was, and then I woke up and there was Selma’s spotty face, and I had a vague hope that everything would be ok. I couldn’t think these thoughts, though. I got where I was, I got in with these kids, to this fort, to this secret place, to these people, by thinking the opposite kinds of thoughts. Thoughts that were deep and cosmic and connected me to the One. Those deep, spiritual thoughts I used to think, for a couple of years where I was done with the costume and I was just happy to be a teen.

So I looked up at Selma, and I was going to try to say something deep, and her face flushed with surprise and her eyes opened wide and she said, “he’s awake! he’s awake!” and I said, “what happened?”

I know, I said people don’t say that when they wake up from being knocked out. They say, “moon jibber?” or “the dogs! the dogs!” or some crazy hallucinatory shit. But that’s people. That’s not me. I’d been knocked out before. I’d practiced. I said, “what happened?”

“You just fell forward, and there was blood coming out of the back of your head.”

“Yeah, but who hit me?” I thought Selma was talking in the way we talked, answering questions truthfully but leaving something out, something we’d claim was unimportant. If you believed that you made your own reality, then what happened was I just fell forward squirting blood because I must have decided that that’s what I wanted to happen, and someone hitting me on the back of the head was incidental to that, or something I’d caused to materialize. Believe me, now I see that this is total bullshit. I knew it then, too. But that’s how we talked, sometimes, in the woods.

But she wasn’t being mystical; she was being literal. As far as Selma saw and heard, there was a thwacking sound and I fell forward bleeding. “Nobody hit you. I didn’t...”

“You didn’t hit me?”

“I didn’t see anyone.”

And that’s when I knew what happened. Someone from the community was fucking with me. I heard a whiny voice say “you should have been there.”

Selma and Keith looked around. They’d heard it too! I could play this.

“That’s for me,” I said. I remembered what I was up to with them, and I said, “That’s the nothing I summoned forth from inside my brain.”

They stared at me. I had a magic fucking power, shitholes, and voices talked to me from the beyond! Fear my ass!

Only, instead, Keith and Selma grabbed each other’s hands and stared at me. Shit. Whatever. Shit.

“I’ve got to go... find my... spirit guide,” I said. My head hurt so bad I felt like puking, but I stood up, dizzy, and pushed off into the woods. “In the woods,” I said. “Selma...” I was going to tell her that she needed to come with me, that the “spirit” wanted her to join me, but you know what? The dizziness and the pain worked on me, and I was out of bullshit and manipulation. I just got up and left while they held hands and stared at me.

“Invisible shithole!” I yelled once I was down the trail. “You should have been there too!”

“He told me to stay away,” said Invisible Boy. He stood in his stupid blue costume, skintight and giving him a wedgie.

Invisible Boy was sort of my friend, back before I found out about being cool. I mean, we’d stand together while Bluejay and Stretch and the others would talk serious shit, and, I don’t know, I guess we were friends. I mean, I never went to his house or got high with him or anything, but part of the story is that we were friends. And now he hits me on the back of the head with a two by four.

“You’re too old for that costume,” I said. It was definitely too tight on him. Gross.

“Stretch told me to stay away from the Engine. Everyone else went. You could have gone. You can fly!”

“How was that going to help?”

“Bluejay would have wanted you to go!”

That was true. Bluejay thought we should be involved in everything. I think it’s how he made up for being so weak: he showed up. If you show up enough times, your chance comes, and you get to be a hero. I mean, Bluejay defeated the AntiMaster. Total fluke, but because he died doing it there was a statue of him in front of The Lighthouse, and the people he’d always wanted to impress acted like he was a big deal, like he was the greatest of them all. That’s what happens when you die: you get what you want.

So Bluejay would have wanted me to go. He’d probably be pretty disappointed that I’d given the whole thing up. But what was the option? Stand around in wedgie-spandex like Invisible Boy? Wash my face five times a day and drink milk and smile when a camera went off? I thought the cheerleaders and jocks were useless idiots, but the sidekicks were even lamer. No thanks. I’d rather have a fort in the woods and a bunch of friends who don’t give a flying fuck about what People Magazine thinks.

“Listen, Invisible, I get that you’re mad. Can you stop hitting me on the back of the head?”

Invisible Boy just stared at me, furious, fists balled up. I hadn’t been in a fight in three years. Nobody I hung out with now thought that beating people up was cool. So when Invisible Shit punched me in the face, it was quite a surprise. I mean, it was a surprise how little it hurt and how quickly I had him in a headlock with his nose in the dirt. Some stuff your body just remembers how to do.

“Don’t,” I said, and let him up. He swung at me again, but this time I dodged and kicked his legs out from under him. Invisible wasn’t much for the face-to-face brawl. When you’re invisible you just sneak up behind people and bop them on the head. You never learn the real shit.

He looked up at me from the duff and I think he was crying. “C’mon, man,” I said.

“No!” he shouted. “No! No! No!”

“It’s not my fault, ferchrissakes! I didn’t build the Engine! I couldn’t have helped! I’d just be dead too!”

“You’d like that,” he said, “you and your stupid friends taking about ‘encountering your own death,’ and ‘meeting with your spirit guide,’ and ‘loving the death that walks beside you!’”

He knew our lingo. He must have been spying on us even before the Engine exploded. Spying on me, I guess.

“You want to get high?” I asked.

“Drugs!” he shouted back, “we fight drug dealers!”

“You do,” I said. “I get high.” I pulled a wrinkly joint out of my pocket and waved it in front of him. “C’mon,” I said, “I’ll introduce you to my friends.” I helped him up and, snuffling, he walked with me back towards the fort.

“Ok,” he said, “but I’m not smoking any drugs.”

Yes, we wouldn’t want you to smoke drugs.

So now there I was, walking with Invisible Boy in his stupid costume, and Selma and Keith see me and their eyes open wide. I thought, this is it. I’m done. Only I forgot something.

“Umm, this man found me in the forest...I’d been...umm...attacked,” said Invisible Boy. Secret identities. Of course he’d protect mine. It was a reflex with our people.

“My spirit guide led me to him,” I said. IB looked confused, but he played along, nodding.

“I thought you… umm, you people were all dead?” said Keith.

“He was,” I said, “They all were. The death I carry with me showed him to me, and let him go. The death needed him alive....” That probably went too far. I thought they didn’t believe me. Whatever.

I sat down on the floor of the fort, and IB joined me. I lit my joint and handed it to Keith and we passed it around. Sharing. It’s a virtue of the pothead. Invisible declined, of course, but I thought he’d see our good ways and we’d have him soon. I mean, who didn’t want to have friends, especially friends this cool?

“So you performed vigilante acts?” said Selma. She sounded non-threatening when she said it, but Invisible didn’t quite understand.

“Excuse me?” he said.

“You attacked criminals?”

“Yes!” he said. He seemed excited to talk about it. I felt bad for him, but Selma just asked questions; she didn’t really give him any shit, or try to make him feel bad. But the whole time, she was leaning against Keith. I didn’t feel too bad about it, though. I had something they didn’t.

Then Conrad walked up, probably tripping. “Who the fuck is this?” he said.

“Sit down,” I said, “he’s cool.”

I didn’t like having Conrad there, especially when he walked once around Invisible Boy. “So what are you supposed to be?” said Conrad.

“He’s a servant of the state,” said Selma. Keith gave her a dirty look. She wasn’t supposed to talk like that anymore. “I mean…”

“What’s with the gay thing?” said Conrad, pointing at Invisible’s wedgie costume.

“Ok, we’re gonna go,” I said. I felt a little protective of IB. These were clearly not his people, and he wouldn’t know how to handle himself here.

“Go where?” said Conrad.

“Go up your ass to find your stash,” I said, and I grabbed IB’s hand and walked down the trail.

“Gay! See! Gay!” said Conrad. What the fuck? Keith collected the worst people in the world. If Conrad didn’t have an infinite supply of coke and mushrooms he’d be as well liked as ass pimples.

We walked down the trail and into the woods. “I want to go home,” said Invisible Boy.

“Where’s home?” Like I said, I’d never been to his house, or really hung out with him at all outside of costume-life.

“Umm, I don’t know if I should tell you.”

“Not tell me? What am I, your arch-enemy? C’mon, it’s just you and me now, nobody else is left.”

“I think some of the west coast guys survived, like,...”

“No way. They called everybody out for this one.”

“Maybe Chicago Sentinel?”

“Ferchrissakes, that guy? He doesn’t even have powers. He’s just something the Chicago chamber of commerce put together so they’d have one of us.”

“There’s got to be a few. We could find them and, umm, start a team?”

“Teams are over. Tell me where you live, I’ll fly you there.”

I hadn’t flown anyone in a long time. It’s weird how you can do something all the time, like go fishing or bike riding or read comic books, and then you just sort of stop doing it, the activity fades out or whatever, and you look back and you realize you haven’t done it in so long you can’t quite remember the last time. You’d think flying wouldn’t be like that, but everything is like that. When was the last time you pretended you were an animal, or climbed a tree? Those things were fun, but somewhere along the line you forget about them. Think about it: you could pretend you were an animal right now. You could get a friend and say, “let’s play that we’re lions.” You could do that, but you don’t, and I don’t know why that is.

But when I thought about flying again, I thought it might be fun. I thought that about climbing a tree just now, too, but I’m not gonna climb a tree. But IB needed to get home, and he was in his costume, and I don’t know. Maybe if Keith had said, “let’s pretend we’re animals,” I would have done that too.

IB’s mom lived out here in the suburbs. I think a lot of us lived outside New York city and just commuted in. I’m pretty sure I saw Wondra at the supermarket one time, and Mister Impossible was my algebra teacher. Used to be, anyway.

So IB turned us both invisible and I put my arms under his armpits and I did the thing that makes me fly. I just lifted up, for the first time in at least a year. We brushed some branches and pushed through the leaves and suddenly we were above the forest. It was really pretty from up here. I could see the fort below us, Keith and Selma sleeping against each other, Conrad sitting in the lotus position and staring fixedly, Lenny walking up the trail to see if anyone was there.

We flew over the remains of the Engine, mostly a big crater, still smoking a little. There were mourners there, weaving pictures of the dead into the chain-link fence, and police officers moving the tragedy-tourists along. A couple of news crews were filming something, and like a million candles were burning all around it.

It was getting dark, and lights were coming on, cars driving home or to the movies, ordinary people who never wore costumes or thought about absolute truth and spiritual being. People with haircuts and plans for what to do on Sunday. And then IB told me we were there and we swooped down into the yard by his shitty little house. It was narrow and needed paint and the yard was crabby and a beat-up Honda Civic was out front. There were a lot of houses like that here. Big rich houses in one area, little shitty ones in another.

“Uh, thanks,” he said.

“Can I come in?”

“I dunno...my mom’s making dinner.”

“So invite me over for dinner.”

“For dinner?”

“Yeah, like we sit and eat and pass the salt and stuff.”

“Don’t you have to go home?”

“I don’t have to do anything.”

“I don’t think my mom would...you look kind of...”

“What, you’re mom doesn’t let you have friends over?”

“You’re not my friend!”

That hurt a little, but I was hungry and I wanted to sit with a family and eat dinner, and I didn’t want it to be my family.

“I’m coming over for dinner. Tell your mom I’m an old friend, or, like, whatever, we know each other, and, um, I, I dunno. I just flew you home, man! You hit me in the back of the head! Twice! Come on!”

IB shrugged, and we turned visible and walked inside.

“Skipper!” his mother shouted, “Why are you in your costume?” Shit, I’d forgotten about the costume. I guess his mom knew about his identity, though.

“Mom, this is...”

“I’m Bird Boy,” I said. Wow, I’d forgotten how stupid that name sounded when you said it out loud. “Old friend of “Skipper,” “I looked at him and smirked. Skipper! So fucking gay!

“Bird Boy! Bluejay’s Bird Boy? Skipper said you do drugs!”

Wow! I guess “Skipper” was kind of a jerk! “Skipper said I could have dinner here?” I asked.

She glared at Invisible Boy who just kind of shrugged, and she rolled her eyes in surrender and exasperation. “Ok, come on in,” she said. She was wearing an apron like a mom from the 50s, and her dingy, tacky little house was full of tacky little ceramics and a cuckoo clock and the smell of meat. “I haven’t had one of Skipper’s super friends over for a while...,” she looked down for a minute, kind of sad, and then said, “Do you boys want to play videogames? Dinner won’t be ready for a few minutes.” Videogames! What was I, five?

“Ok,” said IB, and he led me off to the tiny living room. The couch was ratty and had a knit blanket thrown over it and there was fake wood paneling on the walls. I didn’t have any friends who lived like this. I mean, I’d sit in a plywood shack in the woods or hang out in dirty, abandoned parking garages, but this was too chintzy to be cool.

“Wanna play Nintendo?” said IB.

“I don’t really play,” I said.

“You don’t play videogames?”

“I don’t play, period.”

“So what do you do?”

That was a good question. I got high and I talked and I walked in the woods. I went swimming in lakes, never pools. I broke into uninhabited houses or old institutional buildings. But stuck in a living room, I didn’t do anything.

“I don’t care.”

“You don’t care what you do?”

“I guess not,” I said. “Go ahead and turn on your videogame and I’ll watch.”

IB shrugged and fired up his out-of-date Nintendo and started making a little man run to the right. “Can he run left?” I asked.

“What? Why?”

“I don’t know. You keep running to the right. Why do that?”

“Because that’s the game! You run to the right until you get to the end of the level.”

“Then what happens?”

“You go to the next level.”

“Why?”

“Why?”

“Yeah, why do you go to the next level?”

“Because that’s the game. The game is you run to the right and then you go to the next level.”

“And you never questioned that?” I said. “You never wondered why you wanted to run to the right and go to the next level?”

“No! Why would I...what...I don’t even know what that would mean, ‘question it,’ like, what?”

“I don’t know man. Forget I asked. Just go ahead and run to the right.” I was still a little high, and I just sort of tranced out watching him run to the right, run to the right, run to the right.

“Dinner!” said his mom in a sing-song voice.

“Great, I’m starved,” I said. IB shot me a glance, I don’t know why, and I walked into the kitchen.

There was no dad there. Maybe his dad was dead. I wasn’t gonna ask. His mom had made some kind of meat-and-noodle thing. I remember my dad said that when he was a kid one time he went to a friend’s house for dinner, and it turned out his friend was really poor, and there were like eight kids and two parent and some other grownups, maybe grandparents there, and they were eating spinach. That was it: spinach for dinner. That’s how I felt about the noodle dish.

But I was hungry from getting high earlier so I dug in. His mother cleared her throat really loudly, and I looked up with food in my face and a fork in front of my mouth. She dipped her head and said, “Bless us O Lord for these thy gifts which we are about to receive through the bounty of Christ thy son Amen.”

“Amen,” I said through the mouthful of food, and waited for IB and his mom to start eating. Then I scooped up some more of the oozy stuff and ate. It was delicious. I pretty much had only two kinds of food back then: the overcooked or raw shit my mother passively aggressively made to make us all sick for ruining her life, and the shit I got out of snack machines or at all night diners when I was high and happy and hanging out with my friends. Real home-made food that wasn’t borderline poisonous was a novelty for me.

“This is really good,” I said. “what do you call it?”

“Stroganoff,” she said. “So why do you do drugs?”

Wow. My family never asked questions like that. That just looked at me with disgust. Actually, it was kind of cool that she asked.

“Well,” I said, “it’s like, you see the world, right, through your senses, but how do you know that it’s really the real world? I mean, you’re a mind, in here,” I tapped my head, “and the world’s out there, and there’s just, like, sight and hearing and stuff to tell you it’s real. But then what if they’re wrong? I mean, what if there’s a realer reality, and you don’t know it because you’re seeing it through the doors of perception, and the doors are like, like, dirty windows? And you get high and you see things differently so...”

“Young man,” she interrupted, “drugs will rot your brain.”

I wanted to say something crazy about the truth hiding behind the veil of perception and that kind of shit, same shit I was talking, but I didn’t exactly believe it anymore. I mean, sort of, I wasn’t sure about the whole reality thing, but I was coming to the point where I wasn’t sure, which was very different than the weird certainty that preceded it, where I thought I knew all this secret stuff. So I opened my mouth, like I was going to just start riffing about heaven being visible right here and now if we just opened ourselves to it, the kingdom of God being right here, in this shitty little fucking house full of plaid things, and I was going to just go off, and I didn’t, I shut my mouth, which was weird for me, because I talked a lot of stupid shit back then.

And I ate another bite of the stroganoff, which was delicious, and I wiped my mouth and I said, “Well, that’s your opinion. I mean, I don’t think it’s quite that simple, and I’m not, like, shooting heroin or huffing paint or anything. But I respect your right to, umm, say that, so, ok.”

“And you’re one of them!” she said. I knew she meant the costumed idiots who had all died the other day. All except me and her gay son.

“Yeah, well, that didn’t work out.”

“Skipper is so proud...we’re so proud of him, doing that! For us!”

I started to feel kind of dizzy, like this conversation was heading towards shit I’d rather not think about. I mean, I’d been doing a great job not thinking about it. A lot of people I knew, even if I didn’t really like them, had just died in that explosion, and none of the people I usually hung around knew that I knew them. Keith and Selma and Lenny had no idea, so I had this nice, safe world where I wasn’t grieving, and I just, like, I went into that world, and it was ok. I had other things to worry about there. I felt bad enough there, you know, I didn’t need to feel bad about other stuff. But now with “Skipper’s” mom talking, I started to think about the dead people, the stupid dead people in their stupid costumes who just wanted to help or to be loved for helping. And I felt, like, kind of a lump in my throat, like I might cry. So I took another big bite of the stroganoff and I stood up and I said, “ok, well, thanks for the dinner,” and I started to leave.

Invisible Boy looked really freaked out, like I’d made a major faux pas, and his mom just stared at me like I’d shit on her cat, but I kind of backed up and slid out the front door and then headed down the street. I had about an hour walk to get home, which I didn’t mind. I liked walking at night.

And yeah, I didn’t fly, because, one, I was visible and didn’t want to risk it, and two, like I said, flying was like playing with army men. At some point, you just stopped doing it. So I walked in the dark for an hour, watching police cars go by, and having way too much time to think about me.

James DiGiovanna is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and multiple award-winning film critic for The Tucson Weekly. His fiction has appeared in Spork, Blue Moon Review, and 20X18. In collaboration with Carey Burtt he made the feature film Forked World and the short Kant Attack Ad. His website is www.spoonbot.com.